Share

Don’t miss this window into the ancient world—it’s history you can almost touch.

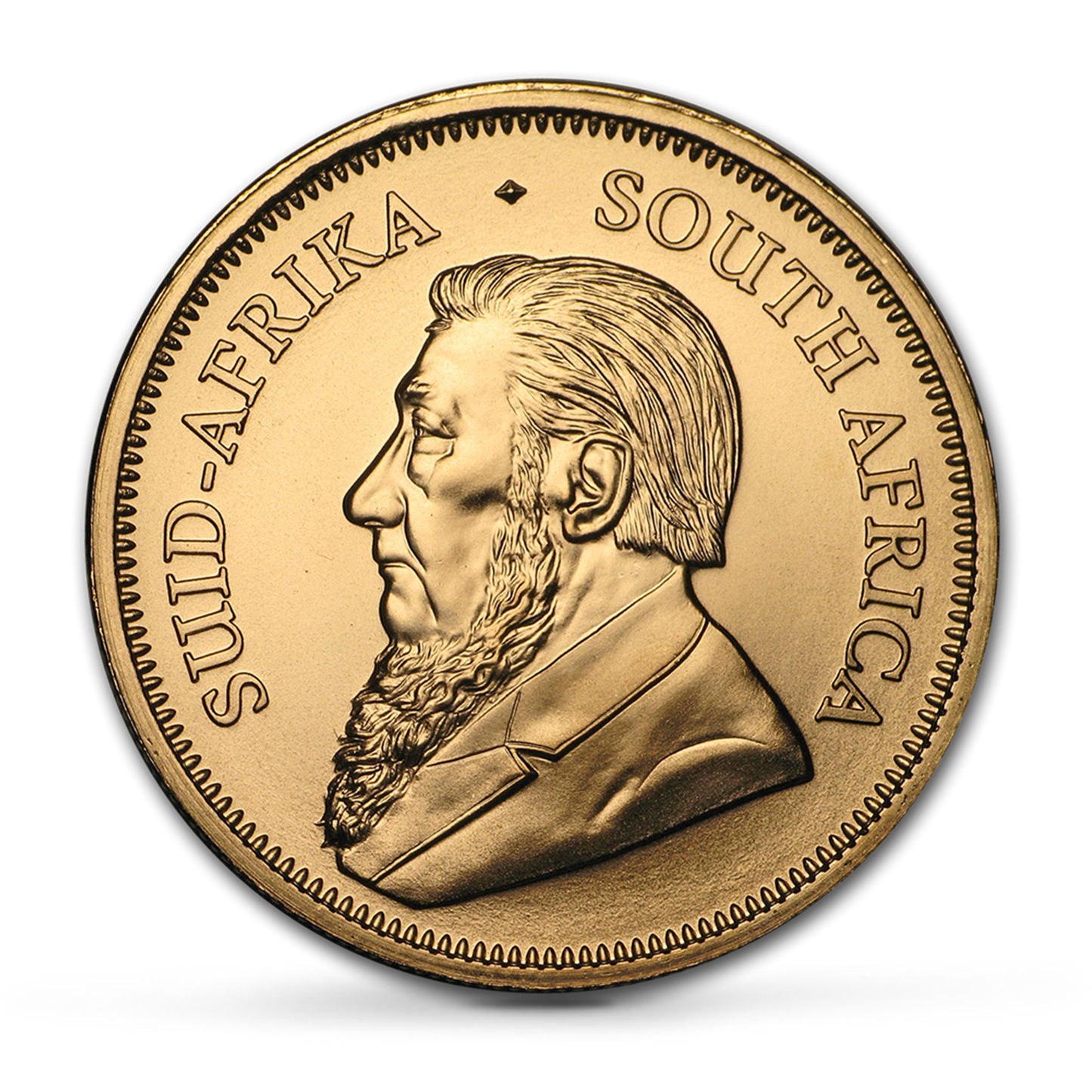

This month, history buffs can marvel at a stunning collection of 404 gold and silver coins from the first century CE, now on display at the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, Netherlands. Part of the “The Netherlands in Roman Times” exhibit, this hoard—unearthed in October 2023 in a muddy field near Bunnik, Utrecht—is the first of its kind found on the mainland of Europe. Discovered by metal detectorists Gert-Jan Messelaar and Reinier Koelink, these ancient treasures provide a vivid snapshot of the Roman conquest of Britain and the interconnected world of the early Roman Empire.

The hoard, a mix of 288 silver denarii, 72 gold aurei, and 44 British gold staters, spans 200 BCE to 47 CE. The Roman coins, some minted under Emperor Claudius and even Julius Caesar, were likely military pay. The British staters, inscribed with “CVNO[BELINVS]” for the Celtic king Cunobelinus, are thought to be war spoils from the 43 CE Roman invasion of Britain. Known to Romans as the “King of the Britons,” Cunobelinus ruled the Catuvellauni and Trinovantes tribes. Some scholars may trace to his successors, Togodumnus and Caratacus, deepening the hoard’s historical significance.

What sets this find apart is its rare blend of Roman and British currency, previously seen only in hoards from Britain itself. Buried along the Lower Germanic Limes, the Roman Empire’s northern frontier in modern-day the Netherlands, the coins indicate that soldiers were returning from Britain with both their wages and looted treasures. Notably, two aurei from 47 CE, untouched by circulation, suggest the hoard’s owner—possibly a centurion or high-ranking officer—received freshly minted coins, perhaps as a bonus for a successful campaign.

Valued at roughly eleven years’ salary for a Roman soldier, the hoard reflects immense wealth. Archaeologists believe the coins were buried in a shallow pit, likely in a cloth or leather pouch, in a wetland area unsuitable for settlement or farming. Was it hidden for safekeeping or offered to the gods in thanks for a safe return? The mystery persists, but the find vividly illustrates Roman military movements between the continent and Britain during Claudius’ conquest.

The discovery’s journey to the museum is a model of ethical archaeology. After finding the initial coins, Messelaar and Koelink reported their discovery to the Archaeology Reporting Centre of Landschap Erfgoed Utrecht. The Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands excavated an additional 23 coins, and archaeologist Anton Cruysheer oversaw their study. The coins were cleaned, recorded in the Portable Antiquities of the Netherlands database, and 381 were acquired by the National Museum of Antiquities for public display.

This hoard reshapes our understanding of the Lower Germanic Limes’ role in Roman campaigns and highlights the era’s cultural and economic ties. It’s a tangible link to a time when Roman legions crossed seas to expand an empire, bringing back stories and spoils. For anyone visiting Leiden, the exhibit is a must-see, offering a chance to stand face-to-face with coins that once jingled in the pockets of soldiers and kings. Don’t miss this window into the ancient world—it’s history you can almost touch.